Test Your Readiness to Provide Nursing Care for Youth with Seizure Clusters Outside of the Hospital

This activity is jointly provided by Medical Education Resources and CMEology.

This activity is supported by an independent educational grant from Neurelis, Inc.

Faculty

Patricia Osborne Shafer, RN, MN

Osborne Health Consulting

Epilepsy Clinical Nurse Specialist, formerly at

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts

Former Senior Director of Health Information

and Resources and Associate Editor of epilepsy.com, Epilepsy Foundation

Introduction

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this educational activity, the participant will be able to:

- Recognize the manifestations of seizures and seizure clusters in youth

- Discuss the fundamental steps in the initial care of a child or adolescent who is having a seizure

- Define the components and purpose of a well-written seizure action plan

- Utilize FDA-approved rescue therapies with a higher level of confidence

It is easy to spot when a child or adolescent is having a seizure.

- The signs of a seizure can be subtle and vary from person to person1

- Recognizing seizures is the first step in diagnosis and treatment

- Delays in diagnosis and proper treatment can result in poor seizure control2,3 and other adverse outcomes3,4

Children and Adolescents with Epilepsy

- Epilepsy is the most common childhood neurologic condition1

- Epilepsy affects about 6 out of every 1000 youth (aged 0–17 years) in the U.S.1

- Youth with epilepsy are more likely to experience mental health, physical health, and school problems than youth without epilepsy1

- Up to 50% of youth with complicated forms of epilepsy have persistent seizures, even on maintenance antiseizure medications2

What May Be Seen in a Seizure

Anything the brain can do normally, can happen during a seizure

- Focal onset seizure

- What happens in the brain depends on where in the brain the seizure starts

- Person may be awake and aware, confused, or unable to respond

- Changes in thinking, emotions, movement, sensation, or autonomic functions may occur

- Generalized onset seizure

- Both sides of the brain are involved at the same time

- Some people may just stare blankly and be unaware for seconds (eg, absence seizure)

- Others may be unaware while stiffening and/or jerking movements occur

- Generalized motor seizures are most common (eg, tonic-clonic seizure)

Seizure Characteristics

- Episodic

- Often sudden and unpredictable: can happen any time and any place

- Most stop in 1 to 3 minutes

- Behaviors during a seizure are stereotypic (are the same each time)

- Seizure length and severity may vary, but what happens is similar each time

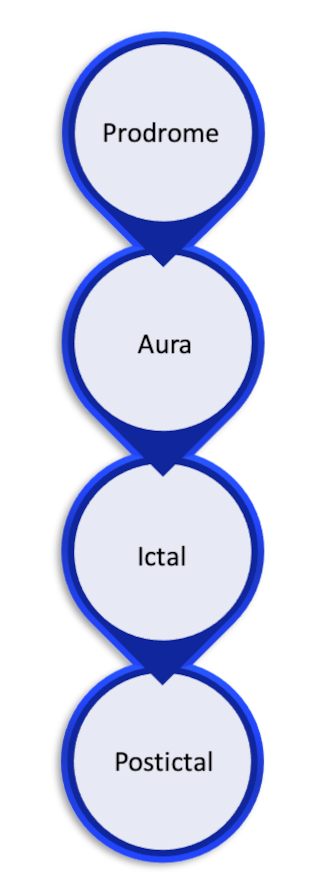

- Some seizures occur in phases that may include1:

- Prodrome: changes in mood or behavior hours or a few days before a seizure; not part of the actual seizure

- Aura: a feeling, symptom, or behavior that is generally the first sign of a seizure

- Ictal: what happens during the seizure

- Postictal: what happens after a seizure; the recovery phase

A person with epilepsy may experience different patterns of seizure activity over time.

- The pattern of a person’s seizures may change over time

- There may be periods in which seizures are longer in duration or more intense

- There may also be periods when seizures happen more frequently, with shorter intervals between each seizure

What Are Seizure Clusters?

- Part of how epilepsy can be expressed

- May be called acute repetitive seizures, serial seizures, or bouts of seizures

- Usually considered distinct or different from a person’s usual seizure pattern

- Any type of seizure may occur in clusters

- Person returns to baseline between the seizures

- May require treatment with a rescue therapy

What Are Seizure Clusters? (cont'd)

- Seizure clusters may be associated with:

- History of convulsive status epilepticus, other seizure-related hospitalizations, and ED visits

- Worse seizure control

- Lost time from work, school, and engagement with activities of daily living

- People use different words for seizure clusters or when to use rescue therapies

- HCPs focus on seizures (eg, number of seizures that occur over a period of time)

- People with epilepsy and their families focus on the impact or experience of seizures. They may use vague terms (eg, multiple, long, or serious seizures, or bad day)

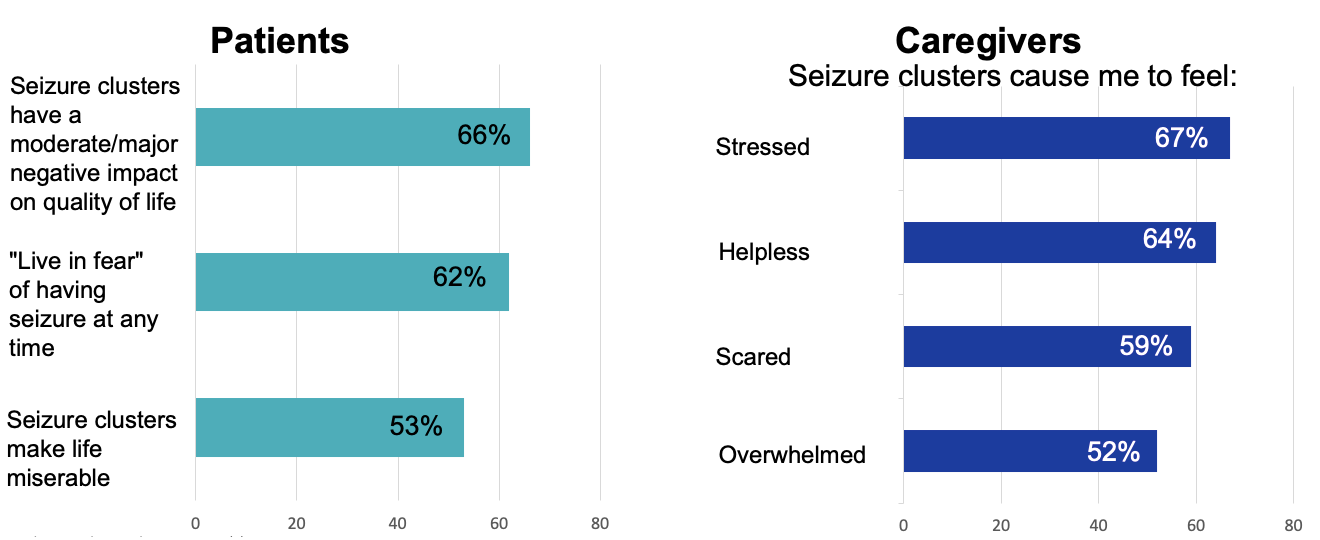

Most Patients and Caregivers Experience Seizure Clusters as a Burden

Data shown are percentages of responses by caregivers (n=263) in the Seizure Cluster Burden of Illness Survey in 2014. Caregivers were asked to assess the impact of seizure clusters on their patient (left) and to describe how they themselves feel when their patient experiences seizure clusters (right).

Convulsive seizures that last more than 5 minutes are more likely to progress into status epilepticus than seizures lasting less than 5 minutes.

- Convulsive (tonic-clonic) seizures that last more than 5 minutes are unlikely to stop on their own1

- Convulsive seizures that last more than 5 minutes are more likely to progress into status epilepticus,1 which can result in death or neuronal damage2

- Rescue therapies are given to stop seizure activity and reduce the risk of progression to status epilepticus3

Seizure Emergencies: What Is Status Epilepticus?

- Definition of convulsive (tonic-clonic) status epilepticus1,2

- More than 30 minutes of either

- Continuous tonic-clonic seizures, or

- 2 or more seizures without full recovery of consciousness between events

- More than 30 minutes of either

- Treatment protocols for status use 5 minutes to define convulsive status epilepticus to3

- Minimize risk of seizures reaching 30 minutes

- Minimize risk of intervening on brief, typical seizures that will stop on their own

- Definition of nonconvulsive status epilepticus1,2

- Includes prolonged or repetitive focal or absence seizures

- Duration is individualized according to seizure type and person’s situation

Status Epilepticus: Key Facts

- Status epilepticus is fatal in about 3% of children and up to 30% of adults1

- The longer status epilepticus lasts, the more likely it is to be fatal2

- Goals of treatment1

- Stop clinical and electrical seizure activity as fast as possible

- Reduce mortality and morbidity

- Benzodiazepine rescue therapies are used to stop seizures that occur in the prehospital setting1

- Follow the person’s seizure action plan for individualized instructions

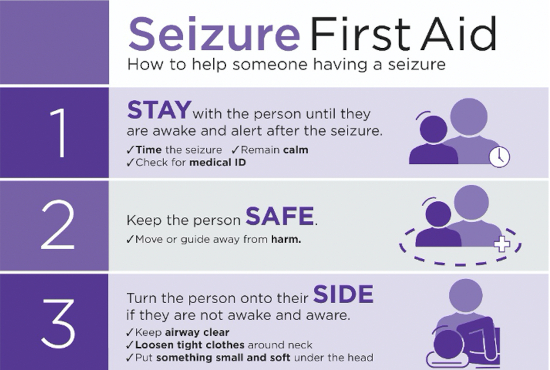

The first steps in seizure first aid are to open the person’s airway and call 911.

- The first steps in seizure first aid are to:

- Stay with the person

- Keep them safe

- Turn them on their side

- Keep the airway clear, but do not put anything in the mouth

- It is not always necessary to call 911 for a seizure

Seizure First Aid

Follow Seizure Action Plan

Use rescue therapy or VNS magnet if prescribed

What NOT to do

- Do NOT restrain or forcibly hold the person down

- Do NOT put any objects in the mouth

- Do NOT give water or food until the person is awake and able to swallow

When to Call for Emergency Help

- Seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes

- Repeated seizures; no recovery between seizures

- Not responding to rescue therapy, if available

- Not returning to baseline after seizure

- Difficulty breathing

- Seizure occurs in water

- Person is injured, pregnant, or sick

- First-time seizure

Seizure Clusters Overview

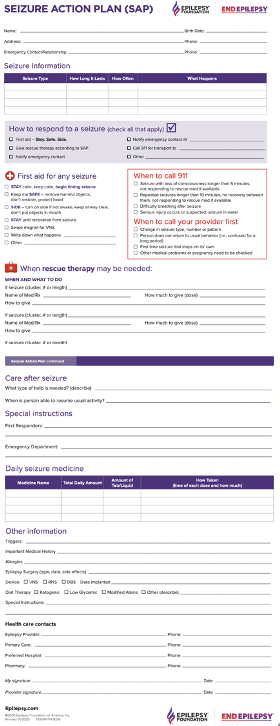

Seizure Action Plan (SAP)

- SAPs are communication tools — they explain how to respond during and after a seizure

- Every person with epilepsy should have one

- Be proactive: create at the time of epilepsy diagnosis, before an emergency occurs

- Anyone can start a SAP, but work together with health care team and caregivers

- Individualize SAP to person’s needs and seizure type

- Include rescue therapy and specify how/when to use

- Keep it current

- Review/update at least annually or with change in seizures or treatment

Seizure action plans can be downloaded at epilepsy.com

Multiple languages; general and school versions available

Case Challenge: Michael

A Seizure Action Plan for Michael

The best time to create a seizure action plan is after a person has been hospitalized for a seizure.

- Ideally, a seizure action plan should be created when the person is first diagnosed with epilepsy

- Seizure action plans should be created before a seizure emergency occurs and before a person needs to be hospitalized!

What Is a Rescue Therapy?

- Antiseizure medicine given prn (“as needed”)1

- Also called rescue therapy2

- Not a substitute for daily antiseizure medications or emergency care1

- FDA-approved rescue therapies can be given by nonmedical people outside of a health care setting2

- Examples of when to use rescue therapies1,2

- To stop seizure clusters or seizures that last longer than usual

- To prevent seizure emergencies

- For change in seizures when triggers or specific situations are identified (eg, when person has viral illness or infection causing change in seizures3)

- Ideally, every person with epilepsy should be assessed for the need for rescue therapy and educated about options2

Rescue Therapies: Communication Challenges

- Risks of uncontrolled seizures and seizure clusters often not discussed

- May progress to status epilepticus1

- Cause greater risk of injury2

- Result in time lost from work, school, and daily activities1

- Gaps in understanding exist among people with epilepsy, families, and health care providers about what seizure clusters are, what words to use, and when to use rescue therapy3

- Seizure action plans improve communication and understanding of how to respond to seizures and seizure clusters4

Caregivers Need and Want More Training

- Education about seizure action plans and rescue therapies is a preferred practice in epilepsy care1

- Yet many caregivers report wanting more education and training

- In the previous survey of 100 families of youth with epilepsy2:

- Only 45% had a seizure action plan

- 87% had been prescribed a rescue therapy...but only 61% said they had been trained how to give rescue therapy

- Caregivers requested

- More hands-on training experience

- Refresher training

- Seizure action plan materials to give to school and other family members

Case Challenge: Maya

- 15-year-old girl with a history of staring spells when younger that resolved

- She now has brief hand twitches and clumsiness (eg, suddenly drops things)

- Recently had a seizure with loss of consciousness and was diagnosed with tonic-clonic seizures

- A daily antiseizure medication was prescribed

- When twitching (myoclonus) and staring (absence seizures) increased, she was seen at an epilepsy center and diagnosed with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

Maya Case Overview

Rescue Therapy Options

- FDA approved1

- Rectal diazepam gel (Diastat AcuDial)2

- Midazolam nasal spray (Nayzilam)3

- Diazepam nasal spray (Valtoco)4

- Non–FDA approved1

- Sublingual or buccal benzodiazepines

- Other benzodiazepine formulations are being developed5

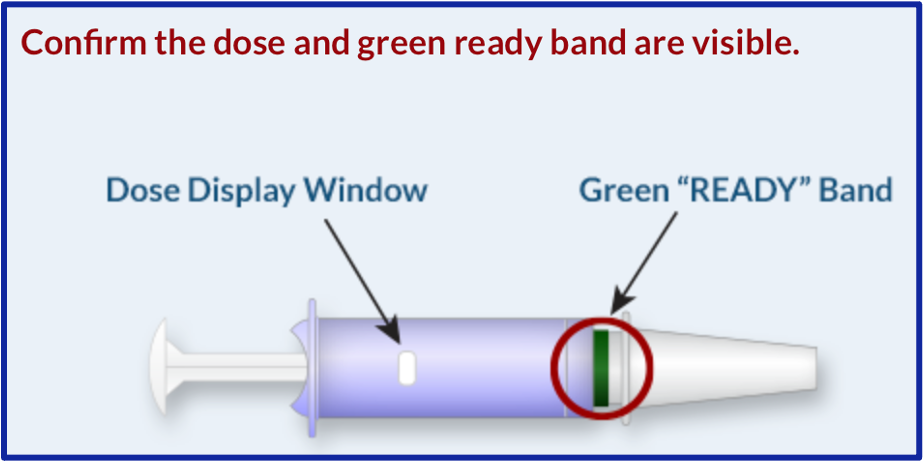

Diazepam Rectal Gel (Diastat or Diastat AcuDial)

- For acute treatment of intermittent, stereotypic episodes of frequent seizure activity (ie, seizure clusters, acute repetitive seizures) that are distinct from person’s usual seizure pattern

- Approved for use in people with epilepsy aged ≥ 2 years

- Pharmacy should set dose (5–20 mg) on syringe

- Dose is based on age and weight

- Confirm dose and green ready band are visible before using

- Adverse effects: somnolence, headache, diarrhea

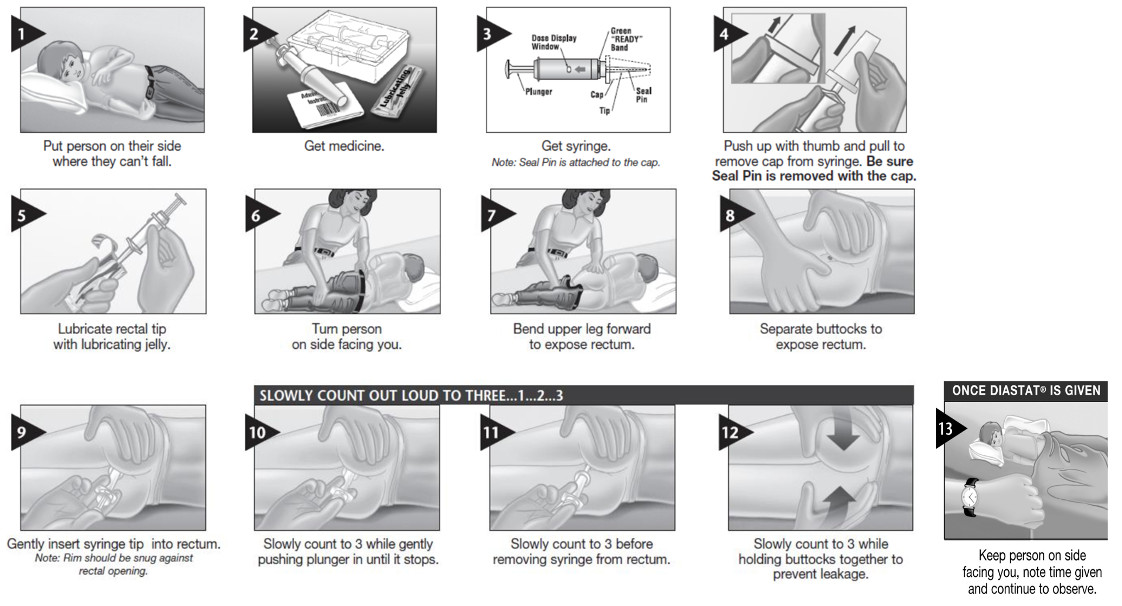

How to Administer Diazepam Rectal Gel (Diastat or Diastat AcuDial)

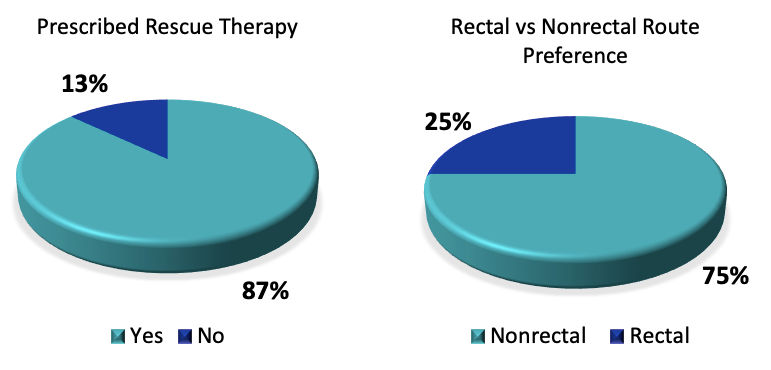

Routes of Administration: Survey Results

Families of youth with epilepsy1

Data from the previous survey of 100 families of youth with epilepsy. 87% had a rescue therapy prescribed. Of 91 families, most (75%) stated they would prefer a nonrectal rescue therapy, and the preference was related to the youth’s developmental status and not to age.

School nurses2

The most frequently reported barrier to diazepam rectal gel use in school was lack of privacy for the student.

|

Student Privacy | 26% |

| Access/availability of RN | 21% | |

| Legal/delegation Issues | 16% | |

| Staff anxiety/fear | 16% | |

| Training non-RN personnel | 13% |

Results from a survey of 419 US school nurses.

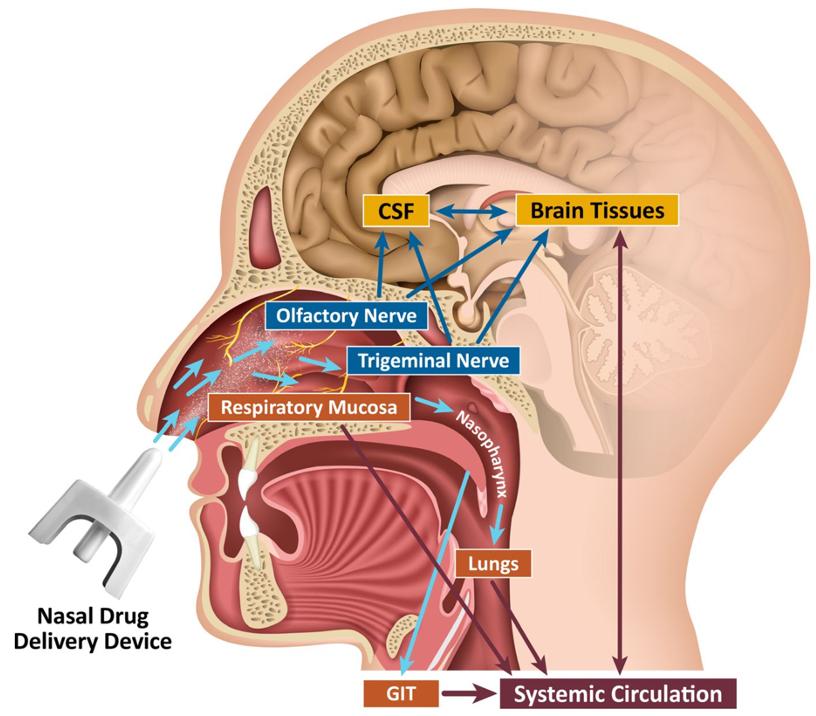

Nasal Benzodiazepines

Advantages

- Rich blood supply gives direct route into systemic bloodstream

- Absorbed quickly

- Faster than injection into muscle (IM) or under skin (SQ)

- Easy to use, convenient, safe

- More socially acceptable for many patients

Disadvantages

- Special delivery device

- Consider head position

- Possible nasal irritation

- Needs open nasal passages

- Can only give small volumes

- Potential for drainage

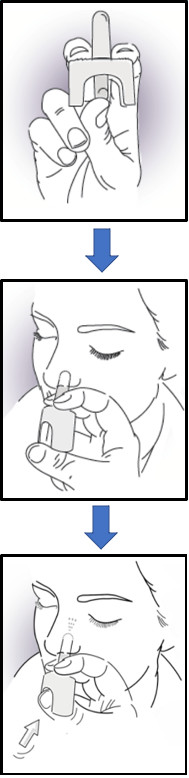

Nasal Midazolam (Nayzilam)

- For the acute treatment of intermittent, stereotypic episodes of frequent seizure activity (ie, seizure clusters, acute repetitive seizures) that are distinct from person’s usual seizure pattern1

- Approved for use in people with epilepsy aged ≥ 12 years1

- Each spray for one-time use1

- 5 mg in 0.1 mL spray

- One spray into 1 nostril

- Second spray used if seizure persists after 10 minutes; use other nostril

- Adverse effects: somnolence, headache, nasal discomfort, throat irritation, rhinorrhea1

- Ethanol, PEG-6 methyl ether, polyethylene glycol 400, propylene glycol, and purified water are used in Nayzilam to increase the solubility and absorption of midazolam2

Efficacy of Nasal Midazolam (Nayzilam)

Probability of not having any seizures during a 24-hour observation period after receiving nasal midazolam for a seizure cluster

- Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

- 204 patients aged ≥ 12 years received either midazolam nasal spray or placebo for a seizure cluster

- Patients who received midazolam nasal spray were more likely to be seizure-free than the placebo group over the 24-hour posttreatment observation period (58.3% vs 37.1%, P = .0124)

Nasal Diazepam (Valtoco)

- For the acute treatment of intermittent, stereotypic episodes of frequent seizure activity (ie, seizure clusters, acute repetitive seizures) that are distinct from a person’s usual seizure pattern1

- Approved for use in people with epilepsy aged ≥ 6 years1

- Dose is based on age and weight1

- Each spray for one-time use1

- 5, 7.5, or 10 mg in 0.1 mL spray

- One spray into 1 nostril

- If 2 devices are needed to give a dose, put 1 spray in each nostril

- Second dose used if needed, at least 4 hours after first dose

- Adverse effects: somnolence, headache, nasal discomfort1

- Intravail A3 and vitamin E are used in Valtoco to increase the solubility and absorption of diazepam2

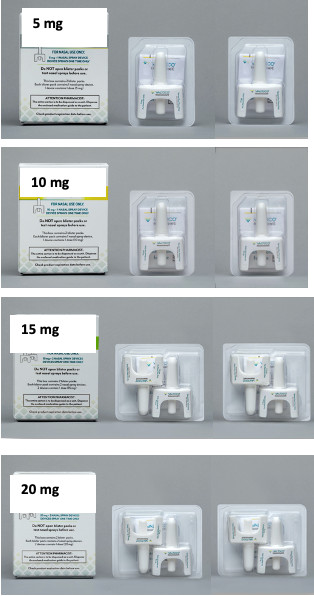

Nasal Diazepam (Valtoco) Dosing is Based on Age and Weight

| 6 to 11 Years of Age (0.3 mg/kg) | 12 Years of Age and Older (0.2 mg/kg) | Dose | Number of Nasal Spray Devices | How to Give a Single Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | Weight (kg) | |||

| 10 to 18 | 14 to 27 | 5 mg | One 5 mg device | One spray in one nostril |

| 19 to 37 | 28 to 50 | 10 mg | One 10 mg device | One spray in one nostril |

| 38 to 55 | 51 to 75 | 15 mg | Two 7.5 mg devices | Two sprays: One spray in each nostril |

| 56 to 74 | 76 and up | 20 mg | Two 10 mg devices | Two sprays: One spray in each nostril |

Nasal Diazepam (Valtoco) Dosing and Packaging

- Each box of Valtoco contains 2 blister packs

- 1 blister pack equals 1 complete dose of Valtoco

- Dose is based on the patient’s age and weight (see previous slide)

- The second blister pack is used if a second dose of Valtoco is needed at least 4 hours after the initial dose

Most Patients Who Used Nasal Diazepam (Valtoco) for a Seizure Episode

Did Not Report Using a Second Dose1

- Valtoco’s effects last for hours2

- A second dose of Valtoco may be given at least 4 hours after the initial dose, if required2

- An open-label safety study looked at how often patients with epilepsy aged 6–65 years reported using a second dose of Valtoco. Each patient was followed for 1 year1

- 3914 seizure episodes were treated with Valtoco in 177 patients1

- Most patients (92%) reported using only 1 dose of Valtoco within the 8 hours following a seizure episode1

- Data shown are from an exploratory interim analysis1

Percentage of seizure episodes (n=3914) for which a single dose was used1

FDA-Approved Rescue Therapies

| Rescue Therapies | Age Indication1 | Dosage Based on Patient Age & Weight1 | Dosage and Administration1 | Bioavailability1 | Peak (Tmax)1 |

Half-life (T ½)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diazepam rectal gel (Diastat) | ≥ 2 yrs | Yes |

|

90% | 1.5 hrs | 46 hrs (parent compound) 71 hrs (active metabolite) |

| Diazepam nasal spray (Valtoco) | ≥ 6 yrs | Yes |

|

97% Less variable systemic exposure than rectal diazepam gel2 |

1.5 hrs | 49.2 hrs |

| Midazolam nasal spray (Nayzilam) | ≥ 12 yrs | No |

|

44% | 17.3 min | 2.1–6.2 hrs (parent compound) 2.7–7.2 hrs (active metabolite) |

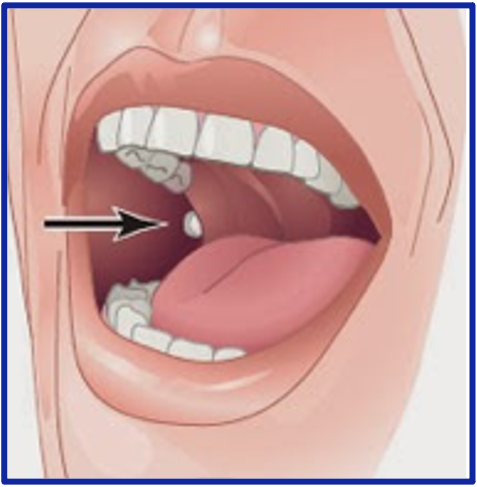

Oral Benzodiazepines

- Not specifically tested or approved by the FDA for use as rescue therapy1

- Typically used for seizure clusters or during times of increased seizure risk (eg, acute illness)1

- Can be placed on tongue (not during a seizure), under tongue, or between gum and cheek2

- May take up to 15-30 minutes to start working2

Care After Rescue Therapy Use

- Turn person on their side after a seizure with loss of consciousness1

- Check airway, breathing, circulation

- Watch for benzodiazepine side effects2,3

- Sedation, disorientation, confusion, amnesia

- Fatigue, weakness, dizziness, unsteady walking

- Rare respiratory depression (slowed breathing)

- Call EMS (911) after rescue therapy given if1:

- Seizure(s) continues or injury occurs

- Difficulty breathing

- Person does not return to their baseline

- If requested by person with seizures or family

- Follow seizure action plan to determine when person can resume usual activity

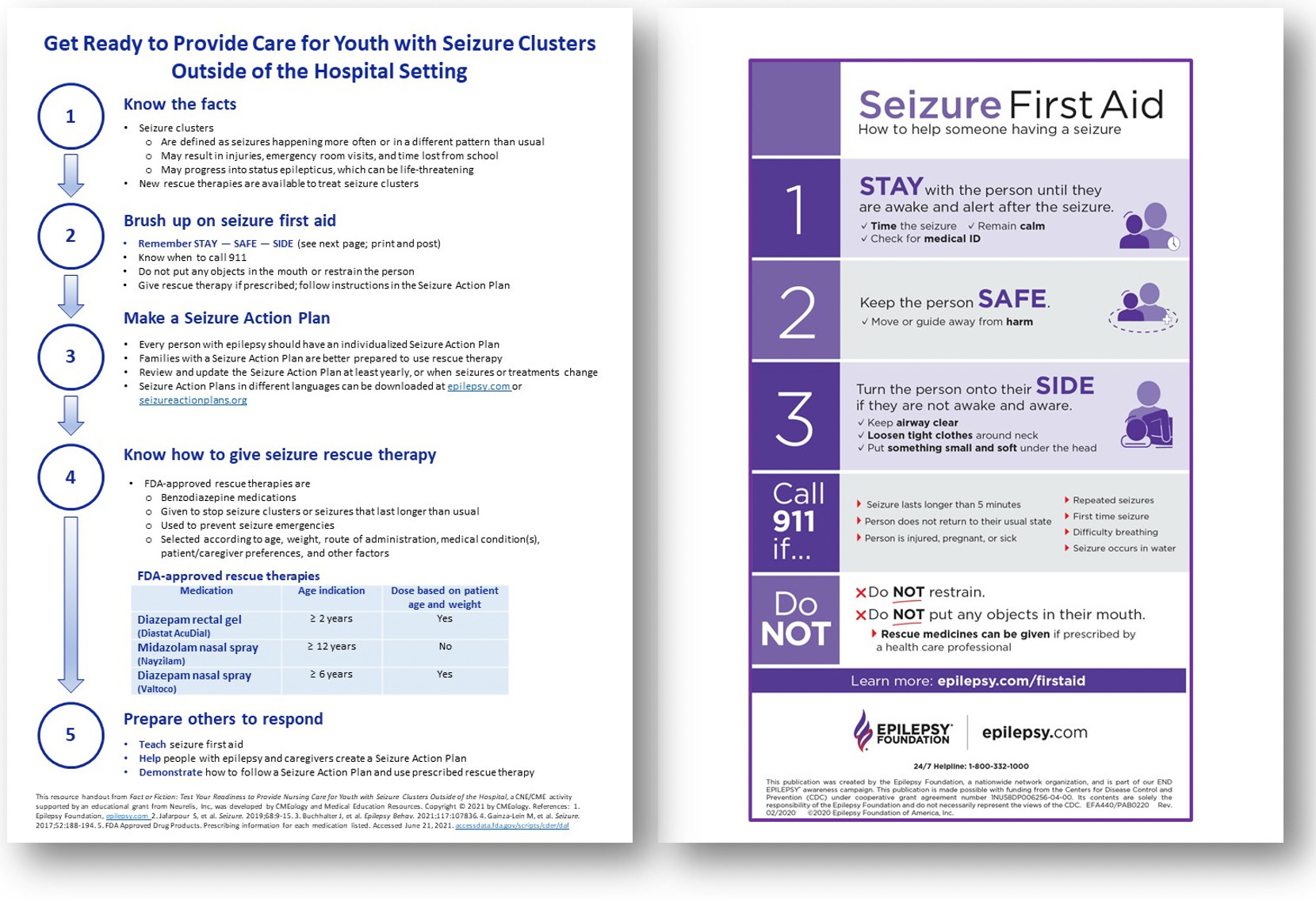

Resource Handout

- Click the link below to download a resource handout that summarizes key points from this activity and contains additional resources

Additional Resources

- Epilepsy Foundation

- https://www.epilepsy.com

- 24/7 helpline: 800-332-1000

- Seizure action plans

- Videos

- Seizure first aid

- How to use different types of rescue therapies

- Seizure Action Plan Coalition